The Seemingly Most Trivial Word Causing Some Nagging Translation Problems.

As mentioned in some earlier posts, there are aspects of the Russian language that leave the translator to her or his own devices in coming up with coherent, true and comfortable equivalents in English. One of these is the fact that the Russian language does not use the definite articles “a”, “an”, or “the” (see post-Banned Articles as Translation Problems). In most cases this a simple matter of judging from the context which, if any, of these needs to be added to the literal translation to make it work in English. In a simple sentence like, for example – “Он уехал в магазин,” which reads literally- “He went to store,” one can safely put a “the” before “store” without compromising the meaning of the original.

As mentioned in some earlier posts, there are aspects of the Russian language that leave the translator to her or his own devices in coming up with coherent, true and comfortable equivalents in English. One of these is the fact that the Russian language does not use the definite articles “a”, “an”, or “the” (see post-Banned Articles as Translation Problems). In most cases this a simple matter of judging from the context which, if any, of these needs to be added to the literal translation to make it work in English. In a simple sentence like, for example – “Он уехал в магазин,” which reads literally- “He went to store,” one can safely put a “the” before “store” without compromising the meaning of the original.

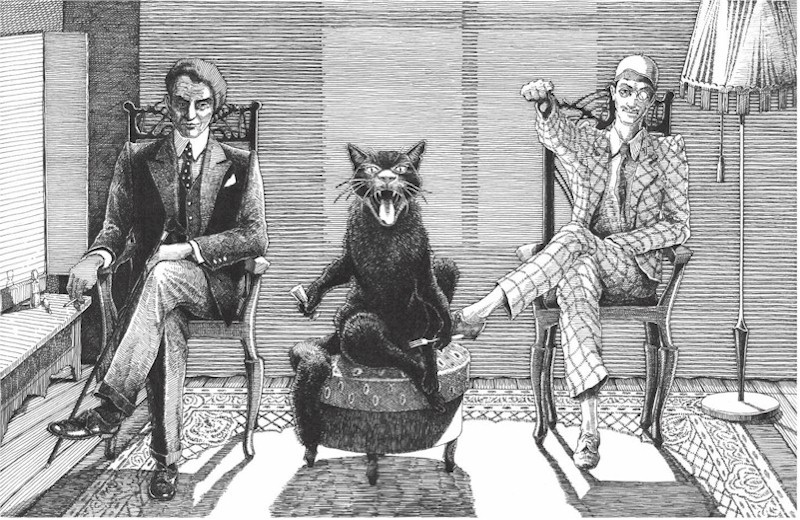

But it isn’t always quite so easy. I am currently bugged by the Russian lack of articles in a specific instance in regards my efforts to write a translation of Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita. This problem presents itself immediately in the title; the English given above is just as it appears in Russian, but the question remains: should it be, as it is in most translations- The Master and Margarita (my emphasis)? And if yes, why? If this title gets an article, why not others: A War and The Peace? The Crime and The Punishment? Continue reading “The Power of “THE””