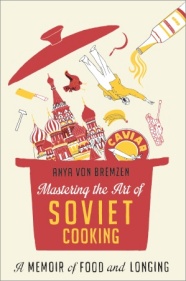

Review—Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: A Memoir of Food and Longing, by Anya von Bremzen

Crown, 2013

On sale—September 17, 2013

One could be excused for imagining that a book with the title Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking might be a collection of recipes, with details about the finer points of food preparation in the former Soviet Union. The subtitle, “A Memoir of Food and Longing,” hints at a more personal account. Neither of these, however, prepare the reader for the epic of family history, biography, autobiography and scholarly assessment of the Soviet Union presented in this excellent new book by Anya von Bremzen, former citizen of the USSR and three-time James Beard Award winner. While this may seem like too much for a single volume, it is artfully stitched together using food, in all its meanings, as thread. The tale of the creation and eventual dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is one of, if not the grandest narrative of the 20th century. Anya’s stories of herself, her grandmother, and especially her mother, are engaging and endearing, and breathe life into the stock of familiar characters and events in the history of the USSR. Her well-crafted distillations of the theses and arguments of prominent academics on subjects such as the “nationalities question” and Stalinist totalitarianism are usually spot-on. All this is brought together by how it informs, and is informed by, food.

Any illusions that this is a book celebrating the quality of Soviet cuisine are quickly put aside when the author admits, in mentioning her mother’s love for sosiski, i.e.- Soviet hotdogs, that “besides sosiski with canned peas and kotleti (minced meat patties) with kasha, cabbage-intensive soups, mayo-laden salads, and watery fruit kompot for desert—there wasn’t all that much to eat in the Land of the Soviets.” Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking is not just about the art of cooking Soviet food, it is about eating food, standing in line for food, parsing ration cards for food, imagining food, remembering food, associating food with people, events and feelings, joking about food, and more.

The book begins by introducing Ms. Von Bremzen and her mother, Larisa, as they prepare, in their émigré apartment in Queens, New York, an homage to pre-revolutionary repasts. This connection with the Empire of the Tsars just prior to the revolution serves as the springboard to a chronology of the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia, from Lenin to Putin, told in the context of the life stories of Anya, Larisa and Larisa’s mother Liza. Through Liza’s experiences we discover what it was like to live in the early years of the newly created USSR. Here we are acquainted with the Bolshevik’s approach to the exercise of political power after they became The Communist Party of the Soviet Union: “Indeed, the turbulent twenties marked the beginning of our state’s relentless intrusion into every aspect of the Soviet daily experience—from hygiene to housekeeping, from education to eating, from sleeping to sex. Exact ideologies and aesthetics would vary through the decades, but not the state’s meddling.”

The subsequent six decades of Communist Party rule are examined in terms of how this relentless intrusion was expressed in the use of food for propaganda and control, and resistance to it manifested in places like communal kitchens and bread lines. In the chapters covering the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s there are two principle characters: Larisa and Joseph Stalin. Fittingly, Stalin is larger than life, strashniy—horrible. His bloodthirsty rule is outlined in all its nightmarish detail: the forced collectivization of agriculture and its attendant famine; the purges that saw the arrest, imprisonment, exile and/or execution of millions; the enforced worship of party, state and of Stalin himself. To convey the “totalizing scope of Stalinist civilization” von Bremzen describes how the Party, through the Food Supply Commissariat, “established and codified a Soviet cuisine canon.”

As counterpoint to Stalin there is Larisa, portrayed in a way that places her among the heroines of classic Russian literature. Like them, Larisa is beautiful, intelligent, alive, and possessed of a strength of character and commitment to personal values that sustain her in a world where the compromise of values is, itself, a value. In the end Anya describes her mother as her “moral compass” in Moscow.

Each of the First Party Secretaries of the USSR is associated with iconic Soviet food or drink. These associations lead to discussions of memorable aspects of their rule. Stalin’s promotion of Sovietskoye Champanskoye—Soviet Champagne—is used to highlight the duality of his constant insistence that life was good for all, against the reality of chronic food shortages. Khrushchev is, of course, remembered for his love affair with corn. His promotion of corn as a miracle grain did little to alleviate the effects of poor harvests, and it was a string of food supply crises that contributed to his fall from power. I was myself provided evidence of this association, and of the persistence of Russian memory, when in 2002 as I gazed out of the window of a train, stopped outside of Moscow because of some delay and surrounded by fields of corn, the provodnitsa (train car attendant) came alongside me, smiled and said simply, “Подарок Никиты Сергейча!”—“The gift of Nikita Sergeyich!” (Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev).

The long rule of his successor, Leonid Brezhnev, is characterized by von Bremzen as an era of mayonnaise. This critical ingredient in the Russian Salat Olivier—an obligatory offering at any celebratory party in the 1970s—is described metaphorically as the “loose cement” tying together the important pieces of a Soviet emigre’s memory.

image from- http://www.yaplakal.com/forum2/st/75/topic495093.html

The last leader of the U.S.S.R., Mikhail Gorbachev, is remembered, and widely reviled, more for his efforts to wean Russians off of their alcohol dependence than for his reforms that ultimately deprived The Communist Party of its monopoly on power. In this chapter von Bremzen provides a detailed and engaging study of the history and rituals associated with the drinking habits of Russians. The book concludes with a collection of recipes of iconic Soviet dishes; one for each decade from the 1910s to the 2000s.

There are some real gems here, too, that give glimpses into more mundane aspects of everyday life in the U.S.S.R., like the descriptions of the many uses for empty mayonnaise jars, and discussions of what the author describes as “the totalitarian Joy of Cooking“—The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, referred to by Soviet citizens as simply, “The Book.”

image from-http://antiqar.uaprom.net/p3818653-kniga-vkusnoj-zdorovoj.html

One thing about Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking that leaves me somewhat disappointed is that life under the Khrushschev, Brezhnev and Gorbachev regimes isn’t examined with the same thoroughness as it is for the Stalin period. To be fair, though, one should not expect an objective treatment of the Brezhnev years, for example, a period known as the “era of stagnation,” to be very exciting. The story picks up again with epic tales of the author, now an émigré returned to her homeland, on a number of road trips with her partner traveling in decrepit Soviet vehicles throughout various republics of the USSR in 1991, when the Union is coming apart at the seams. This account ends with Gorbachev’s televised resignation address on Christmas Day 1991, and an epic case of alcohol poisoning.

Early in Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking, there is a discussion of the meaning of the Russian word byt, roughly translated as “everyday life,” but which the author explains is “a deeply Russian concept, difficult to translate.” She tries by asserting it signifies “the metaphysical weight of the daily grind, the existentially depleting cares of material living.” Reflecting on this, I decided her book could be described as an account of people trying to master the art of Soviet byt. Or not; in the end, Larisa decides that the solution to the problems of living in the Soviet Union, problems exacerbated for Soviet-Jews, was to get herself and her daughter away, to emigrate. In 1974 they leave the USSR and settle initially in Philadelphia.

Toward the end of the book, the author imagines children in Moscow today pleading with their grandmothers: “Babushka, babushka, tell us what it was like living in the USSR!” I feel like one of these kids. At least since I was a teenager growing up in the time of the Cold War I have wanted to know the truth about life in the Soviet Union. With Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking, Anya von Bremzen has given us a masterful telling of this story.

© 2013, John Dougherty. All rights reserved

Is this book available in Russian language?

Paul, I’m not aware of a Russian version by Ms von Bremzen, or a translation. You could try to contact about this.