What’s in the Brown Paper Bag? Just Some Dostoevsky, Chekhov and Karamzin.

A media fascination with works of Russian literature delivered to Edward Snowden, the American NSA analyst turned leaker/defector, burst forth today with speculation as to why certain books were included, and what Snowden might take from reading them. I feel compelled to join the fray, mainly to point out some important elements of this story that have, as far as I’ve read, been missed.

Articles on the websites of The New York Times and the LA Times make some interesting observations. Each of these articles focuses on one of three books reportedly given to Mr. Snowden yesterday, July 24, 2013, by Anatoly Kucherena, a Russian attorney advising him on his asylum request and acting as his spokesperson. Of two of the books, Julia Ioffe writes in the New Republic: “Today, Kucherena said he brought Snowden a copy of Dostoyevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment’, and some Chekhov ‘for dessert.’ It’s time, he said, for the young man to learn about our reality.”

Robert Mackey, in his post of yesterday to The Lede blog on The New York Times website, looks at the third author, Nikolai Karamzin—“The Third Man on Snowden’s Reading List.” Mackey wonders what Snowden might learn about Russian reality from this conservative historian and author of 200 years ago, who argued extensively that autocracy was the one indispensible political system for the success of Russia in the world. Referring to Harvard Professor Richard Pipes’ translation and analysis of Karamzin’s “Memoir of Ancient and Modern Russia,” Mackey muses that perhaps the inclusion of Karamzin is meant to acquaint the reader with the political sensibilities of Russia’s ruler today, Vladimir Putin, working with the presumption that, “Inasmuch as Putin is both a conservative and a nationalist, he very likely admires Karamzin’s History.” I myself made a similar connection in my post to this blog in November 2012—Russia and the Rest—but there I discussed the Russian attitude toward autocracy as part of the larger picture of Russian identity; pointing to it as one part of Russia’s response to the modernization occurring in Western Europe. I argued that this response to the increasing power of the West did much to inform the development of Russia’s national identity.

Unfortunately, we do not learn from Mackey’s post which of Karamzin’s works Kucherena offered. Karamzin was an immensely prolific writer of fiction and poetry as well as history.

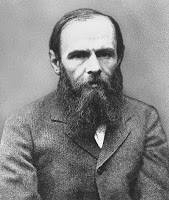

In her article on the LA Times website—“Snowden, reading ‘Crime and Punishment,’ may see his own plight”—Carol J. Williams points out that “in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment,’ the marooned National Security Agency leaker may find an echo of his own moral musings, if he has any, over his decision to disclose NSA snooping on the personal communications of millions,” and she gives a brief synopsis of the novel to highlight her point. I have some problems with her comparisons, not the least of which is, that unlike Rodion Raskolnikov, Snowden’s crime did not involve killing old women in their apartment with his own hands. Also, the motive she ascribes to Raskolnikov is incomplete. She writes that, “the impoverished university dropout convinces himself he is doing society a service by killing the old-crone moneylender Alyona Ivanovna, whom he sees as a leech feeding on the down and out like himself.”But like most of Dostoevsky’s characters, Raskolnikov is much more complicated. An essential element to his motivations is his conviction that ends justify the means. He has plans, vague as they may be, to do great things with the money he has gotten from his crime. Ms. Williams also reduces the character Sonia to “another social victim, a young woman forced into prostitution to support her family,” who convinces Raskolnikov “to confess and face the punishment for his crime.” She ignores the critical point that Sonia is also a devout believer in the Russian Orthodox faith, and as such holds the promise of Raskolnikov’s salvation.

My take on these two authors, Karamzin and Dostoevsky, is that they both provide important insights into how Russians identify themselves vis-à-vis the West. After the horrors of the French Revolution and the catastrophic invasion of Russia by Napoleon, Russians came to see their own Tsarist autocracy as part of what made them unique, and superior, to Western Europe. This became an important belief in the Slavophile camp of Russian intellectuals. Another important element of this conviction that Russia’s strengths lie in adherence to those values that set her apart is Russian Orthodoxy. Writers like Tolstoy saw the simple life of the peasant, and the faith that sustained them as part of what made them morally and ethically superior. In Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov is seduced by Western ideas learned at University. He becomes self-centered and loses the Russian-ness of his soul. It is Sonia’s undying faith that offers redemption.

Nearly 200 years ago Tsar Nicholas I proclaimed,on the occasion of uprisings in the Empire’s Polish provinces, the essence of Russia in three words—”Orthodoxy, autocracy and national unity!” Many today see Putin’s style as autocratic, and as such he would make Karamzin smile. The importance of Orthodoxy is seen in his advertizing the monk, Father Tikon, as his spiritual advisor, and the prosecution of members of Pussy Riot hinged on their desecration of a church as much as their criticisms of Russian politics. Like Raskolnikov, Pussy Riot was seduced by the ideals of the corrupted West–things like freedom of speech and expression.

Whether Kacharena’s intention or not, these authors from the 19th century, Karamzin and Dostoevsky, can help a foreigner understand the reality that is Russia today.

And now for dessert! Anton!

© 2013, John Dougherty. All rights reserved

Small correction: “Orthodoxy, autocracy and national unity” was a doctrine, formulated by Sergei Uvarov, Minister of Education and President of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

And Putin, as authocratic as he is, is hardly a nationalist. If anything, he is anti-russian nationalist.