With two dreams, one after another in Master and Margarita, Bulgakov touches on some risky subjects.

As mentioned at the beginning of my last post (“Sympathy for the Devil in Russian Literature”), my efforts to translate Chapter XV of Master and Margarita, “Nikanor Ivanovich’s Dream,” led me to become fascinated with the use of dreams as a device in Russian novels. My first avenue for delving into this topic further was Dostoevsky’s use of it in The Brother’s Karamazov, specifically the chapter titled, “The Devil. Ivan’s Nightmare.” This provided not only another example of a dream sequence, but also another depiction of the devil, so I devoted that last post to a comparison of Dostoevsky’s devil with Bulgakov’s.

I remained intrigued, however, by the dream thing. As I began translating the next chapter of Master and Margarita, “The Execution,” I was delighted to find that I was dealing here with yet another dream—this one dreamt by Ivan (Bulgakov’s Ivan, not Dostoevsky’s); two dreams in a row!

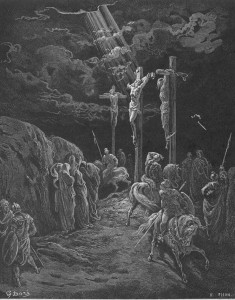

Now that I’m finished with both chapters, it occurs to me that the use of dreams by Bulgakov may have been an attempt to get around state censorship, and avoid criticism from powerful interests such as the Writers’ Union. In both chapters, controversial or unacceptable views are put forth— but in ways that allow the author to argue something like, “I’m not saying that this is the way it went down; this is simply the way this character dreams about it.” In Chapter XV Nikanor Ivanovich finds himself part of a theater production that is at the same time an effort to accuse male citizens of illegally keeping foreign currency, and to encourage them to confess and give over their goods to the authorities—quite literally a “show trial.” In the next chapter, Ivan dreams of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, as if he himself were there, but the details of this dream offer some important deviations from the standard narrative derived from the gospels.

but in ways that allow the author to argue something like, “I’m not saying that this is the way it went down; this is simply the way this character dreams about it.” In Chapter XV Nikanor Ivanovich finds himself part of a theater production that is at the same time an effort to accuse male citizens of illegally keeping foreign currency, and to encourage them to confess and give over their goods to the authorities—quite literally a “show trial.” In the next chapter, Ivan dreams of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, as if he himself were there, but the details of this dream offer some important deviations from the standard narrative derived from the gospels.

Chapter XV begins by pointing out that the “the man with the crimson face,” (mentioned in a previous chapter as a new patient at the same psychiatric clinic that Ivan had earlier been brought to against his will) was Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoy, another unfortunate victim of the mysterious “consultant” and his gang. But before visiting Doctor Stravinksy, the director of clinic, Nikanor Ivanovich “made a preliminary visit to another place.” This “other place” is almost certainly an office of the NKVD—predecessor of the KGB, or secret police—as we see Nikanor Ivanovich subjected to interrogation regarding the foreign currency (specifically U.S. dollars) found hidden in his apartment. He insists this was planted there by an evil power that has taken up residence in his building. Soon he becomes hysterical, has hallucinations, and the interrogation ends when: “It became entirely clear that Nikanor Ivanovich was not fit for any kind of conversation.” He is then taken to the clinic, put in his own room, and sedated. He finally goes into a deep sleep and has this dream, which “was based, undoubtedly, on his experiences of that day.”

Nikanor Ivanovich finds himself in a small but opulent theater, with a packed audience consisting exclusively of men with beards. The “show” is emceed by a handsome, well-groomed young man who constantly jokes with, needles, pleads with, and harangues his guests, demanding that they confess and give up their currency. There are a series of “acts,” one starring Nikanor Ivanovich himself, in which participants either confess their wrongful hoarding of foreign currency (and/or precious metals or jewels), or are confronted with undeniable evidence of their guilt. Nikanor Ivanovich neither confesses nor is proved guilty, so he is asked to again take his seat at the end of his act. Apparently each member of the audience is presumed guilty, as the only way to leave the theater is to confess all, and reveal the location of illegal goods. The allusions to actual proceedings orchestrated by the Communist Party—with “witnesses,” “confessions,” and lectures about the duty of citizens to not be selfish but to devote themselves to advancing the Revolution, with the guidance of the Party—seem obvious. That this “theater” represents a prison is indicated, according to one “Master and Margarita” website, by certain details: “In theatres men and women are not segregated by sex, in prisons they are. The beards could be because the prisoners couldn’t shave, or they could be a hint that the foreign currency speculators are Old Believers, like many merchants were, or Jews.” Though, of course, this is just one character’s dream.

This dream ends with Nikanor Ivanovich shouting in his sleep, “Nothing! Nothing! I have nothing! Do you understand! Nothing!” Although he is calmed with another injection, his anxiety is said to spread to the other rooms in the psychiatric hospital, causing upset there as well. Here the story nicely segues from the first dream to the second:

“But the doctor quickly calmed the heads of the anxious and depressed, and they began to fall asleep. The last of all to drop off was Ivan, when over the river it was already getting light. From the medication, lubricating his whole body, comfort came like a wave covering him. His body was relieved, and the sandman blew with a warm breeze about his head. He fell asleep, and the last thing he heard from the real world was the predawn chirping of birds in the forest. But they soon fell silent, and he began to dream that the sun was already going down on Bald Mountain, and that the mountain was surrounded by a dual cordon…”

In this way Chapter XV, “Nikanor Ivanovich’s Dream,” ends with the beginning of Ivan’s dream, and Chapter XVI is devoted entirely to the story of the execution of Yeshua Ga-Notsri (Jesus of Nazareth) as Ivan sees it in this deam. The detailed descriptions of the scene at Bald Mountain and the actions of the Roman cavalry and centurions there are stunning, and for much of the chapter do not seem to contradict the gospels in any significant ways. But the activities of Levi Matvey (Matthew Levi, one of the twelve apostles) and those of a mysterious man wearing a cowl are a departure from the gospel narratives—at least as far as I was made to understand them. Levi is completely devoted to Yeshua, believing himself to be responsible for his capture; he is determined to spare him from the torture and suffering of execution by killing him, if he cannot free him. But it is near the end of the chapter when things get really good. By now it is near the fifth hour of the execution; all of the onlookers—inhabitants of Jerusalem and pilgrims who have come for the celebration of the high holiday of Passover—have gone back to the city because the spectacle is not very interesting, and preparations for the holiday festivities are under way in town; a huge thunder cloud has swallowed the sun and threatens to strike Bald Mountain; the Roman soldiers are hastily preparing to leave; at the order of the mysterious man in the cowl, one of the executioners stabs each of the three being executed in turn, so that the Romans won’t have to wait around for them to die; the man in the cowl pronounces the three criminals dead; then the Roman forces rush back to Jerusalem just as the rain and lightning hit the mountain.

No one notices that one civilian, Levi Matvey, is still on the mountain. When all of the Romans are gone, he proceeds to cut the ropes binding Yeshua to the cross, and, as an afterthought, releases the other two bodies as well. The chapter ends with this scene:

“A few minutes passed, and on the hill there remained only these two bodies and the three empty poles. The water thrashed and shifted these bodies.

By this time neither Levi nor the body of Yeshua was on the summit of the hill.”

This is more than a slight modification of gospel accounts. From the gospels it is believed that one Joseph of Arimathea asked for, and received, permission from Pilate to take Jesus’ body and bury it in his own tomb. Joseph personally, possibly with the help of Nicodemus, removed the body from the cross and entombed it, sealing its entrance with a boulder. But of hugely greater importance is the fact that, though pronounced so by the mysterious man in the cowl, it is unclear if Yeshua is actually dead at this point. If he didn’t die on the cross, this account undermines the central tenet of all Christianity. But again, this is only a dream.

While Nikanor Ivanovich’s dream of “show trials” provides clever criticism of the Soviet regime’s far from fair and impartial judicial practices, Ivan’s dream is more tightly woven into the story of the novel. Whereas the first of the two dream chapters begins and ends with the dreamer awake, “The Execution” chapter begins and ends in the dream, in a way making it less dreamlike. This presentation of the latter also makes it a continuation of the “consultant’s” account of Pilate’s meeting with Yeshua on the morning of the crucifixion, told to Ivan at Patriarch’s Ponds in Chapter II. Chapter III begins with the last line of the consultant’s tale, and Ivan—only now realizing that hours have gone by—at first thinks that he must have dreamt it rather than heard the consultant tell it. This story of Pilate’s meeting and Ivan’s dream of the crucifixion are significantly connected by the presence in each of the mysterious man in the cowl. They also both relate to an important element in the book’s plot concerning a novel about Pontius Pilate, written by the “Master”—a work for which he suffers persecution at the hands of Moscow’s literary elite. So, parallel to the story of the arrival of Satan in Moscow in the 1930s, there is this peculiar version of the well-known story of the passion of Jesus Christ. I suspect that that the consultant’s story and Ivan’s dream may turn out to be verbatim excerpts from the Master’s novel.

With two dreams dreamt by two different characters, presented in sequence in Master and Margarita, Bulgakov touches on some pretty daring subjects. The use of this technique, combined with the blatant and continual absurdity, makes this novel simultaneously delightful and important.

© 2014, John Dougherty. All rights reserved